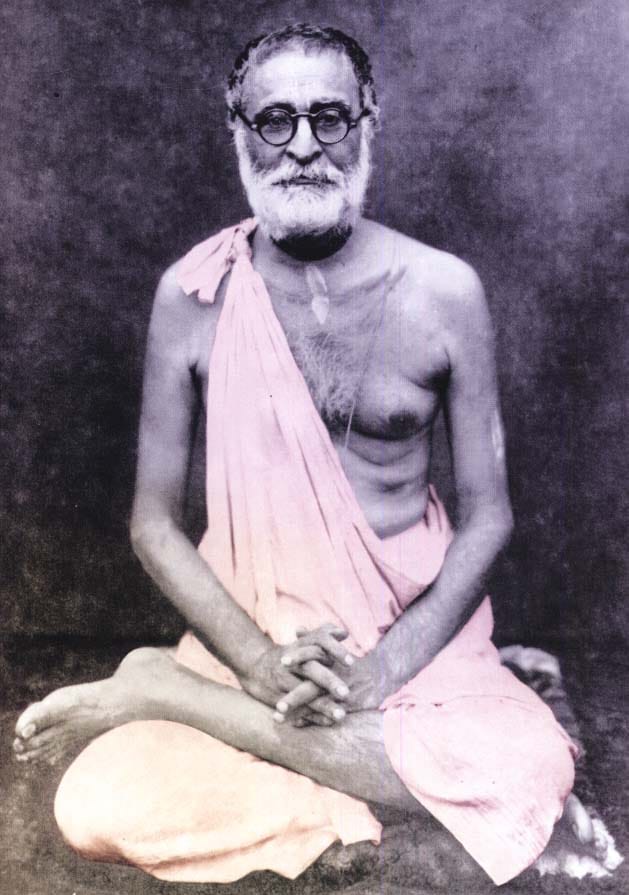

Śrī Siddhānta Sarasvatī, Transcendental Archaeologist, and the Mystery of Chernobog and Belobog

Looking through Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura's bibliography the other day, I found the curious heading "Pratīcye kārṣṇa sampradāya (The Lineage of Krishna in the West)" in Year 7 of the Gauḍīya, Issue 28, page 443:

I've attempted a faithful translation below:

A Kṛṣṇa Tradition in the West

“Some time ago, the Kingdom of Montenegro was famous for becoming one of Europe’s twenty-nine nations. This Montenegro is full of mountain ranges. The indigenous residents of these mountains are of unparalleled courage. It was the Italians who gave this region a name that means ‘kṛṣṇa-parvata’ (black mountain) in their language. At one time, the Aryan people migrated from the prāgbhūmikā (ancient lands or easterly regions) of Asia to these western regions and established settlements around this kṛṣṇa-parvata, which came to be called Jārṇā Gora by its inhabitants. Though called Jārṇā Gora in the Slavic language, it was called ‘Kṛṣṇa-giri’ in Sanskrit. In one context, referring to color, the word ‘kṛṣṇa’ means black, but in relation to the land, it refers to ploughing or digging. The indigenous farmers of this Kṛṣṇa Mountain cultivated the earth with the aim of pleasing the deity Jārṇā Bhoga. Professor Ernest P. Horwich suggests that the term “Jārṇā Bhoga” can be translated in Sanskrit as “Kṛṣṇa Bhagavān”. Even today this Kṛṣṇa Mountain is consecrated to Lord Kṛṣṇa. This indicates the existence of a Kāṛṣṇa tradition even in such a distant region. Professor Horwich is a Sanskrit professor at the University of New York and the University of Dublin, and a comparative linguistics professor at the universities of Bombay and Rangoon. Since 1928, he has been working with the Bombay Government as a researcher in the field of Indo-Iranian linguistics.”

Let’s break this down section by section with a little bit more information:

1 - Basic History

“Some time ago, the Kingdom of Montenegro was famous for becoming one of Europe’s twenty-nine nations. This Montenegro is full of mountain ranges. The indigenous residents of these mountains are of unparalleled courage. It was the Italians who gave this region a name that meant ‘kṛṣṇa-parvata’ (‘black mountain’) in their language.”

(a) First referred to as Montenegro in the late 15th century by the Venetians, the region became recognized by that name as an official kingdom in 1910 but became part of Yugoslavia after the First World War, gaining internal recognition in July of 1922, which is likely what Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda is referring to in his introductory sentence. Or he is perhaps referring to Montenegro’s involvement in the outset of the First World War.

(b) American anthropologist Christopher Boehm, who lived in Montenegro and studied its tribes up to 1966, noted that the barren, mountainous terrain of Montenegro itself contributed towards what he called “a refuge-area warrior society”. Major Steven C. Calhoun writes: “The low scrub and poor, rocky soil made a pastoral existence the best means of subsistence. Further, the rugged terrain provided distinct defense or escape advantages. […] This social structure proved flexible enough for a variety of military actions from a small raid to a larger territorial defense involving thousands of warriors. The patriarchal and hierarchical leadership of clans and tribes also adapted well to military actions as the need arose. Further, Montenegrins valued their autonomy and had a highly developed sense of honor which committed them to defend their land rather than submit to Ottoman rule.”1

(c) The name Montenegro is a Venetian calque, or loan translation, of the Serbian “Crna Gora”, which literally means “Black Mountain”, owing to the dark evergreen forests covering Mount Lovcen.

2 - Ancient History

“At one time, the Aryan people migrated from the prāgbhūmikā (ancient homeland or easterly regions) of Asia to these western regions and established settlements around this black mountain, which came to be called Jārṇā Gora [Crna Gora] by its inhabitants. Though called Jārṇā Gora in the Slavic language, it was called ‘Kṛṣṇa-giri’ in Sanskrit.”

Here, Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda is likely referring to the Illyrians, an ancient race of Indo-European-speaking people of whom we find earliest mention in the 5th century. The Illyrians are described as having worshipped the Sun as their main deity, depicting it as a geometric figure, with either spirals, concentric circles, and the swastika, or with the images of birds, serpents, and horses.2 It seems that Indo-Iranian religious traditions came into Montenegro through both the Illyrians and the Slavs. According to Boehm, the tribes of Montenegro are descendant mostly from Slavs who settled the Balkans before the 10th century.3

3 – Origins of Crna Boga, the Black God

“In one context, referring to color, the word ‘kṛṣṇa’ means black, but in relation to the land, it refers ploughing or digging. The indigenous farmers of this Kṛṣṇa Mountain cultivated the earth with the aim of pleasing the deity Jārṇā Bhoga [Crna Boga]. Professor Ernest P. Horwich suggests that the term “Jārṇā Bhoga” can be translated in Sanskrit as ‘Kṛṣṇa Bhagavān’. Even today this Kṛṣṇa Mountain is considered consecrated to Lord Kṛṣṇa. This indicates the existence of Kāṛṣṇa tradition even in such a distant region.”

Note that Śrīla Sarasvatī Thākura seems to have spelled Crna Boga [or Chernobog] phonetically above. Crna/Cherno: Max Vasmer’s dictionary traces the etymology of the word chernyy: “black” from the Proto-Indo-European *kerǝs- , cf.: lit. Kirsnà (river name), Old Prussian. kirsnan “black”, Old Indian kr̥ṣṇás “black”, hereafter lit. kéršas “black and white, spotted”, kéršė “motley cow”; Sw., Nor. harr - the same (proto-German *harzu-). Boga/Bog: “riches, wealth, abundance” in Indo-Iranian languages, [see “ṣannam bhaga itinganā” Viṣṇu Purāṇa 6.5.47]; baga means “share” in Avestan; and “God” in Slavic languages.

Chernobog [Zcerneboch/bothe in Latin] first appears in 12th century Christian monk Helmold’s description of Polabian Slavs of eastern Germany worshipping two gods: one of good fortune and one of misfortune. While many scholars recognize the theonyms Chernobog and Belobog as found throughout Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Czech, Bulgarian, and German, others discount these notions, claiming Chernobog was a Christianization, a pejorative name for the devil, likely influenced by polarized Zoroastrian ideas of the struggle between good and evil. Others insist that while Chernobog and Belobog may have been Christianized as God and the devil, they belonged to an older tradition of the Slavs that revered them equally and understood them to have complimentary energies.

“Before conceptualisation as Rod, the supreme God was known as Deivos (cognate with Sanskrit deva, Latin Deus, Old High German Ziu, and Lithuanian Dievas). [“Deva-deva jagannātha…”] The Slavs believed that from this God proceeded a cosmic duality, represented by Belobog (“White God”) and Chernobog (“Black God”), representing the root of all the heavenly-masculine and the earthly-feminine deities, or the waxing light and waning light gods, respectively.[1]”

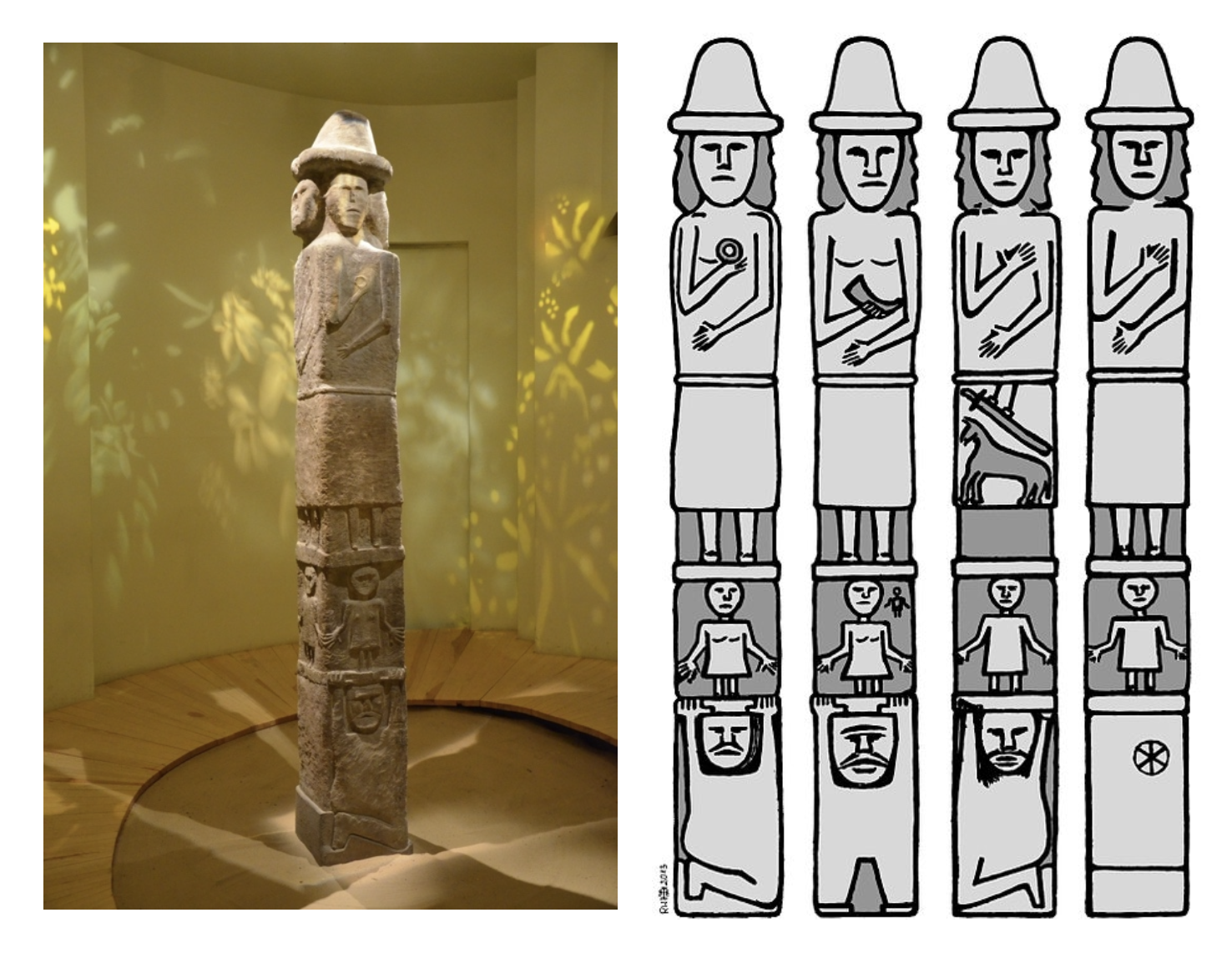

While this may be the outright claim of Slavic neopaganism, scholars differ in their opinions of who was the original god of the Eastern and Southern Slavs (Ukraine, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, etc.). Some scholars, like Boris Rybakov, do favor Rod, whose name is thought to derive from a Proto-Indo-European word meaning “root”. Some have noted the similarity with the Avestan word rada, which means “guardian” or “keeper”. He may have been depicted as having four heads (see “Zbruch Idol”). Other scholars criticize this idea of Rod’s supremacy and claim Perun was the only pre-Christian god of the Slavs. In any case, the position of Rod was eclipsed by Perun (from Indo-European root per or perk “to strike”, “splinter”, associated with the Vedic Parjanya, Baltic Perkūnas, Albanian Perëndi, etc.[2]), a god of lightning and thunder.

The student of the Bhāgavata can step back here and perhaps discern the presence of the Vedic trinity of Caturmukha Brahmā, Garbhodakaśāyī Viṣṇu, and Rudra. Though scholars have rejected any connection between Rod and Rudra, if we take into consideration Śiva’s role as the upādāna-kāraṇa, linking him to the Old East Slavic connotations of the word rod, which are “generation, birth, origin, etc.”[3], we have a strong case.

Add to this a curious detail mentioned by Rybakov: the rosette, or “seed of life”, as it is better known today, represents the hypostases of Rod, his underlying essence. The rosette or hexafoil is interpreted as the symbol of Ishtar or Uṣas, the Dawn Goddess, later Christianized in Russia as the Ognyena Maria “Fiery Maria”. She is a sister to Perun, as Uṣā is to Indra, and rides in this fiery chariot (pictured below) of “The Word”. Uṣā, or Sarasvatī, was known as Vāk Devī (Goddess of Speech). She is the śakti of Śrī Kṛṣṇa imparted to Brahmā to give him a glimpse of the spiritual world so that he may create the fourteen planetary systems, seven higher and seven lower (the seven interlocking circles of the hexafoil?). Though Rudra, who is the incarnation of Viṣṇu’s sudarśana-cakra (also oft represented by a hexafoil symbol), protected Uṣā from Brahmā, for some reason he did not save her from Indra (Perun) who, in a bizarre act of vengeance or ceremony that has long puzzled Vedic scholars, later shattered Uṣā’s chariot as she rode across the sky.[4] It is curious that the symbol for Perun’s thunderbolt also resembles the rosette. There are stories here as old as the creation of the cosmos, stories of rivalries between cosmic deities and weapons like the sudarśana-cakra, the most infallible weapon of all, followed by Śiva’s triśula, Brahmā’s brahmāstra, and lastly, Indra’s vajra. How interesting that Brahmā’s boons repeatedly empower various Daityas who can then overpower Indra and his vajra and usurp the throne of Svarga. Was Brahmā perhaps delivering indirect punishment to Indra for attacking Uṣā?

As we can see proof of here, the Slavic mythology is considered the most faithful to the original Proto-Indo-European religion—and therefore indispensable for understanding those ancient religious roots of many, many other traditions—largely because the Slavs maintained their religion rather than letting it be altered by intellectual or political elites.[5] They tenaciously resisted Christianization and, even when Christianized, wove their old religion into the new one imposed on them.

The genesis of Chernobog and Belobog from Rod then parallels Pādma creation by Viṣṇu, followed by Brahmā’s contribution, leading to the run-in with Rudra (the necessary force of destruction), and followed up by Indra’s affront. This lines up with the stories told in the Bhāgavata and other Purāṇas. It also calls to mind the descriptions in Viṣṇu Purāṇa, Mahābhārata, and Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam of Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma as Mahā Viṣṇu’s, or Sadāśiva’s, śveta (white) and kṛṣṇa (black) hairs incarnating to quell the asuric oppression of the Earth. As these statements contradict the central Bhāgavata teaching of Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s supremacy, they can only be accepted as poetic devices used to mislead the asuras. Considering the confusion around the origins of Chernobog and Belobog, it would seem this was accomplished, keeping the tattva of Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma partially obscured, allowing for numerous confusions and conflations.

Mahā Viṣṇu, Brahmā, and Rudra were conflated into Rod and then replaced with Indra; Indra, as the white god of the heavens was conflated with Brahmā or Viṣṇu and seen as the ultimate god, while Vṛtra and Garbhodakaśāyī Viṣṇu, who sleeps on Ananta-deva in the Garbhodaka Ocean at the bottom of the universe, were conflated into a serpentine evil. (As per Slavic mythology, Perun, who dwells in the upper reaches of the cosmic oak tree and is oft represented by an eagle, battles Veles, a watery serpent of the underworld.) Later Balarāma and Indra were conflated as the Good God, the “Biel Bog,” and pitted against Kṛṣṇa, who was relegated to being a dark, devilish serpent inhabiting the netherworlds again.

These confusions and conflations were only possible due to ignorance of Viṣṇu’s status as Sarveśvareśvara, the God of Gods, He who rides on the eagle and sleeps on the serpent, the Lord of both Asuras and Devas, of both Vṛtra and Indra. Here we can easily line up the Zoroastrian parallel of Zurvan (from sarva “all, the one”) who generates the polarities of Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu with the Slavic Rod who generates Chernobog and Belobog. Bereft of the nirmatsarānāṁ satāṁ, or harmonizing guidance, of the Sātvata āmnāya, of Vyāsa Muni, Christianity inherited these dichotomies and added its own flavour, which culminates with Disney portraying Chernobog as this:

But no harm done. Those who cannot conceive of an omnipotent God who is simultaneously the source of all that is beautiful and terrifying must compromise their logic and faith and create such dichotomies to understand the world and their place in it. The haṁsas, however, the swans, lead by the Paramahaṁsas like Śrī Siddhānta Sarasvatī, can separate the milk from the water and retrieve the whole essence.

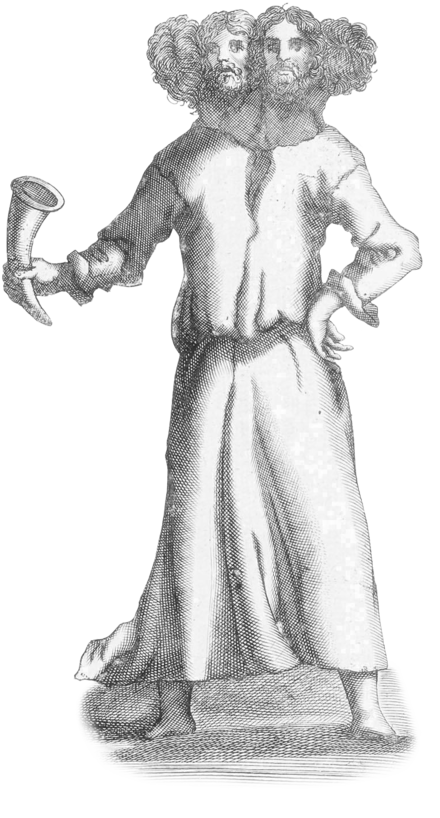

4 - Svetovit, Belobog — The White God

Speaking of milky white—known as the older “White God”, a god of abundance and war, Svetovid, or Belobog, bears a curious resemblance to Baladeva, depicted always with a horn (filled with liquor). Supposedly the word svet meant “strong, mighty” in Proto-Slavic language, while the suffix vit is either Proto-Slavic for “lord, ruler” or Germanic for “warrior, hero” and is perhaps linked to the Sanskrit word vitati “to invite, to wish health, to expand”. Ovit could also mean “he who has much of something”. And Svet could be retraced to Sanskrit words like śvānta “peaceful”, śveta “white”, or sva anta “one’s heart” (“svānta-sthena gadābhṛta”). His depiction with four heads could be explained as his representation of the Catur-vyūha, which seems to make an appearance in the ancient Slavic Zbruch Idol, Sviatovid (“the world-seer”), mentioned above—though scholars insist that Svetovit is not to be confused with Sviatovid. If you look at the images on the pillar, however, you see one figure holding a ring (or cakra), one holding a horn, the other standing above a horse and sword, and the last figure not holding anything discernable.

Traces of the cult of Svetovit can be found throughout Russia, Ukraine, Serbia, Croatia, Germany, and Iceland and may have eastern counterparts in the cults of Baal and Belun. More relevant to the topic at hand, however, literary theoretician Radoman Kordic writes quite plainly of Svetovit/Belobog and Chernobog worship in Serbia:

“The Serbs had two main gods: Vida (Svetovid, Belobog) and Crnobog, the god of light and the god of darkness, the underworld. However, which of them was the primary one is not clear — or perhaps they shared power equally. According to Iranian cosmogony, from which they supposedly originated, the priority should be given to Vida. Maybe it was indeed like that. Scholars tend to believe in it. Likely, Vida was within the framework of some kind of approved, recognized religion, officially the first god. However, it seems that Serbs did not always acknowledge that position, and they even carried out a revolution in the divine world. The place of Vida was taken by Crnobog, at least for some time and permanently among a part of the Serbs.

“The significance of this revolution (or periodic revolutions, which could be part of the religious system, i.e., anticipated and legitimate) must have been significant. The Serbs perceived it as betrayal and the murder of the father. Language memory, if we can rely on it, and it seems that we have no more convincing witness, confirms this. Even today, a father or mother might say to a son who has committed some wrongdoing: "Black son, why did you do that?" I cannot delve into this saying in detail here. However, I can assert that, even if it does not directly invoke Crnobog, which is still likely, it evokes the ancient pattern of division. The black son has betrayed the ideal, betrayed, chosen another father, carried out a revolution in the divine world.”[6]

Or—rather than a biblical revolt against a heavenly father god by a dark devil—perhaps these impressions started out as something simpler: a disagreement between brothers, like the one between Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma prior to the Mahābhārata War. As the repercussions of the Mahābhārata War were felt across the old world, as the armies of the Scythians, Greeks, and others who sided with Kauravas were decimated, largely by Kṛṣṇa’s orchestrations, He surely garnered considerable reputation as a force of destruction and a cunning strategist. Contrasted with the image of Baladeva, which was likely conflated with that Indra or Perun as well at some point, the polarization of Baladeva being good and white and Kṛṣṇa being bad and black starts to make sense.

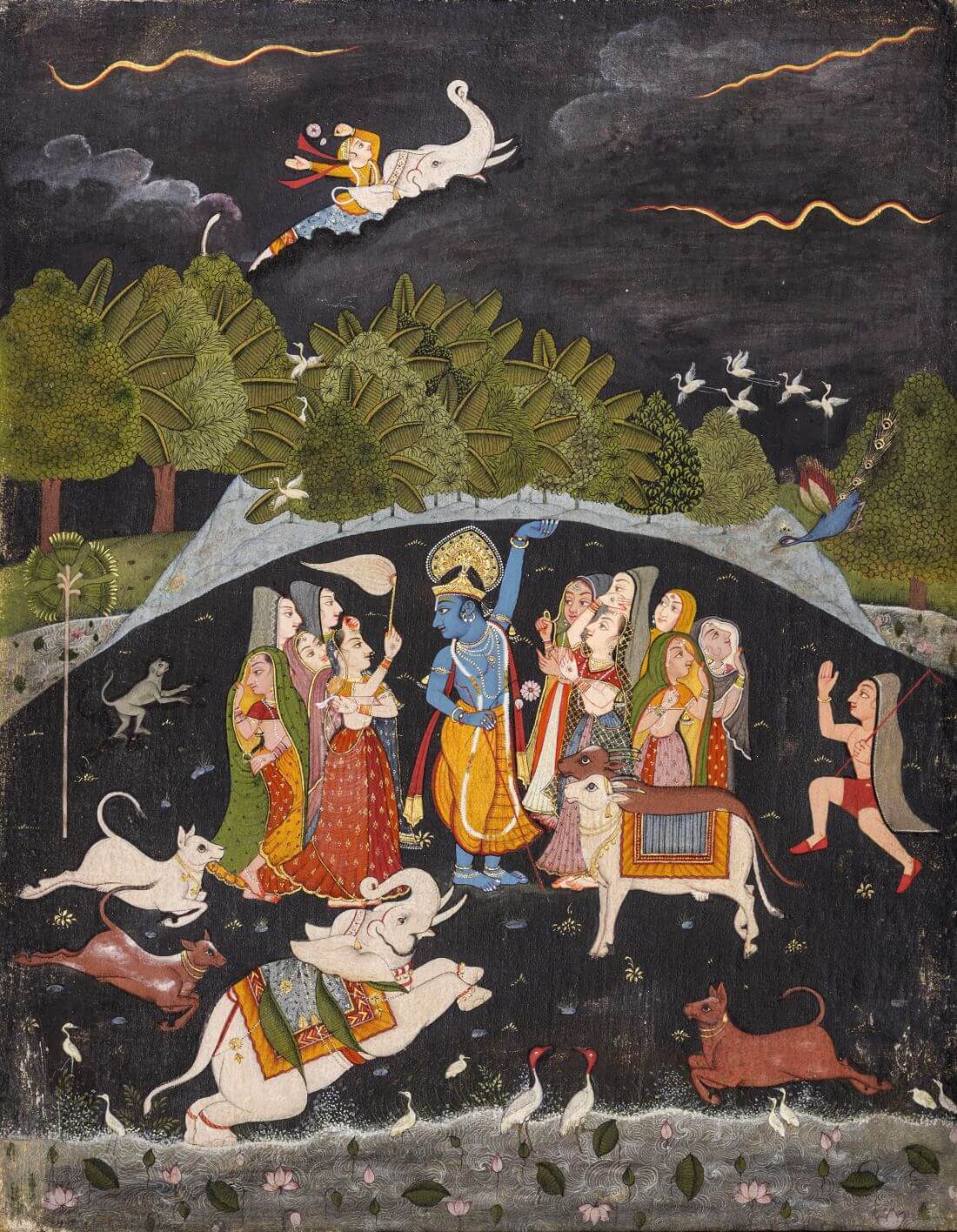

5 - Of Dragons and Pastoral Villages

Along the lines of more naravat, or human-like, explanations, it is possible that the Slavic impression of Rod or Perun being the originator of Chernobog and Belobog comes simply from Parjanya Mahārāja, the grandfather of Kṛṣṇa and Balarāma, and the associations with Indra have more to do with the gopa tradition of Indra worship. When Kṛṣṇa put a stop to this, He carried out a revolution against a light and life-giving god of the high heavens by worshipping and literally elevating a mountain, Śrī Girirāja Govardhana. As per Vedic lore, the massive dragons like Vṛtra and various flying mountains had long been mutilated by Indra’s thunderbolt. Only one such creature, Mainaka, it is said, managed to escape and hide in the ocean. When Śrī Giridhārī Kṛṣṇa raised Govardhana and saved the inhabitants of Vraja from the devastating storm sent by Indra, He curbed Indra’s pride by using the scion of Indra’s old foes, thus promoting Govardhana to the status of Girirāja, the king of mountains, for having restored the honor of his dynasty.

Is it at all curious then that certain Kṛṣṇa-worshipping warrior/gopa tribes in far-off Montenegro would name a mountain after Kṛṣṇa and, as Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura mentioned, offer or consecrate (utsargī-kṛta) that mountain to Him, or perhaps even identify the mountain as Him, as Vaiṣṇavas do with Girirāja Govardhana?

And there is a strange legend in the region that bears eerie resemblance to some reiteration of the Govardhana-līlā. It tells of specially empowered dragon-like defenders of villages who ward off dangerous hailstorms and the like:

“A zduhać, or vetrovnjak (Vṛtra?) in Serbian tradition, and a dragon man in Bulgarian, Macedonian, and southern Serbian traditions, were men believed to have an inborn supernatural ability to protect their estate, village, or region against destructive weather conditions, such as storms, hail, or torrential rains. It was believed that the souls of these men could leave their bodies in sleep, to intercept and fight with demonic beings imagined as bringers of bad weather. Having defeated the demons and taken away the stormy clouds they brought, the protectors would return into their bodies and wake up tired. The zduhaći are recorded in Montenegro, eastern Herzegovina, part of Bosnia, and south-western Serbia.”[7]

“A significant mythological figure encountered by the heroes is the Fire Dragon or Črt. It is a very common occurrence in Slavic mythology, where the dragon was considered a male serpent, larger and more malicious, and therefore more dangerous than a snake. Katičić mentions that the word "zmaj" (dragon) originates from the Proto-Slavic poetic language, and both poetic and ritual texts described it as a being connected to the earth, a chthonic (earthly) demon, ploughing the earth and dragging furrows, unpleasant and dangerous. (Katičić, 2017: 77)

“Sučić also mentions the Dragon, but he calls it Čort or Čert. The specific role of the “zduhač” in the production of anti-subjects directly calls to mind the role that rightfully belongs to Vid’s high priest. Isn’t this also the reason why the belief in the “zduhač” persisted precisely in the regions where the cult of Crnobog prevailed?”[8]

How curious that these “dragons” are connected with ploughing and digging the Earth, which is one of the interpretations of the verbal root kṛṣ, and the zduhač endured wherever Crnobog was worshipped?

Certain influential person, like the Prince-Bishop of Montenegro, Petar I Petrović-Njegoš, who was instrumental in creating the foundations of the South Slav unification movement that indirectly led to the outset of World War I, was also said to have been zduhaći. Lo and behold, Njegoš chose, as his last wish, the aforementioned Kṛṣṇa-giri, or Mount Lovćen, as his final resting place.

While some of these connections may be a bit of stretch and I may have strayed or erred at any number of points, I pray that the swan-like paramahaṁsas will be able to syphon up the sublime truth of the universal Vaiṣṇava tradition that is oft lost in the murky waters of time and ever-changing culture.

Here, Paramahaṁsa-kula-cūḍāmaṇi Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura has, line by line, given the essential information needed to chart a course through what is possibly one of most drastic distortions of the perception of Kṛṣṇa, and one that we, as Kṛṣṇa devotees, are familiar with when accosted by hardline Christian rhetoric that suggests, nay states, that Kṛṣṇa is the Devil. It turns out they are not just being fanatical or hardline; they have reason to believe this because of the way Kṛṣṇa’s story has evolved along the centuries and across regions of the world—and how those of asuric natures tend to view Him. Kṛṣṇa’s pastimes are indeed difficult to understand and can be polarizing. As mentioned in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (10.43.17), when Kṛṣṇa enters the wrestling arena of King Kaṁsa, He is perceived in a variety of ways by different viewers: the wrestlers see Him as a bolt of lightning, Kaṁsa sees death itself, the women see Cupid, etc.

In this case, the switch of Vedic demigods to demonic beings in Zoroastrianism and the idea of good vying endlessly with evil, which influenced Christianity, seems to have played a pivotal role in these perceptions. And then, of course, there were the repercussions of the Mahābhārata War.

While Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura made a point of writing a small comment about this, he did not make a big deal of it, nor did he get embroiled in tracing and retracing the ancient mythologies. He detected something of a far off and possibly lost Kṛṣṇaite tradition and pieced together enough information to draw a simple and clear conclusion that holds up to scrutiny today: a people in the wilderness of Montenegro living a rugged pastoral existence, ploughing the Earth, worshipping a dark-complexioned God, revering a mountain as sacred to this God—and maybe cultivating special siddhis to fight off devastating hailstorms? Was this ancient settlement some kind of neo-Vraja of its time? What kind of kṛṣṇa-bhaktas were these? Fierce yoga-miśra-bhaktī-practicing Aryan Slavs? Was Mount Lovćen revered as Girirāja Govardhana? And was it Śrīla Sarasvatī Ṭhākura’s transcendental affinity for Śrī Śrī Gāndharvikā Giridhārī that led him to reveal this? Let me know what you think.

Jagad-guru Oṁ Viṣṇupāda “Kṛṣṇa-preṣṭhā” Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura Prabhupāda ki jaya!

Sources:

[1] Gasparini, Evel (2013) “Slavic Religion”. Hanuš, Ignác Jan (1842). Retrieved from Wikipedia, Dec 30 2023.

[2] Jakobson, Roman (1985). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter.

[3] Mathieu-Colas, Michel (2017). "Dieux slaves et baltes"

[4] Callaso, Roberto (2021). Ka – Stories of Mind and Gods of India. Knopf.

[5] Jakobson, Roman (1982). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter.

[6] https://radomankordic.com/Zduhach_Psihoanaliza_teksta Univerzitetska riječ, Nikšić, Naučna knjiga Beograd 1990.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zduhac [Retrieved Jan 1 2024]

[8] Korman, Marin (2020). “Tragovi slavenske mitologije u pisanoj tradiciji novije hrvatske književnosti”, University of Zagreb.